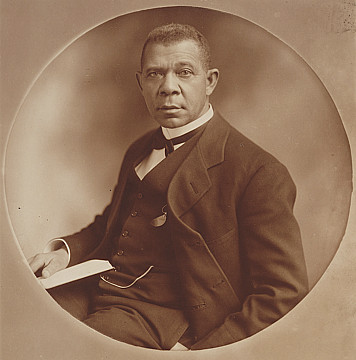

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915)

Civil Rights Leader & Founder of the National Negro Business League, etc.

He was born into slavery, on the small tobacco plantation of James Burroughs in Franklin Co., Virginia. His mother, Jane, was Burrough's cook and it is thought that his father was a white man from a nearby plantation. After emancipation in 1865, his family moved to West Virginia, where he worked in salt furnaces and coal mines while pursuing education. His determination to improve himself led him to Hampton Institute in 1872, where he worked as a janitor to pay his tuition and absorbed the school's philosophy of industrial education. In 1881, he founded the Tuskegee Normal & Industrial Institute in Alabama, starting with just thirty students in a small building.

Under his leadership, Tuskegee grew into a prominent institution promoting practical skills and self-reliance for African-Americans. He believed vocational training would provide economic independence and gradual social advancement for Black Americans in the post-Reconstruction South. He rose to national prominence with his 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech, where he advocated that African-Americans should focus on economic progress and vocational skills rather than making an immediate demand for political rights and social equality. This conciliatory approach won support from white politicians and philanthropists (eg., Julius Rosenwald and Mary Wanamaker Warburton) but drew criticism from activists like W.E.B. Du Bois, who favored direct confrontation.

Under his leadership, Tuskegee grew into a prominent institution promoting practical skills and self-reliance for African-Americans. He believed vocational training would provide economic independence and gradual social advancement for Black Americans in the post-Reconstruction South. He rose to national prominence with his 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech, where he advocated that African-Americans should focus on economic progress and vocational skills rather than making an immediate demand for political rights and social equality. This conciliatory approach won support from white politicians and philanthropists (eg., Julius Rosenwald and Mary Wanamaker Warburton) but drew criticism from activists like W.E.B. Du Bois, who favored direct confrontation.

Despite his public stance, he secretly funded legal challenges to segregation and disenfranchisement. He became the most influential African-American leader of his era, advising Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Taft on racial matters, and his autobiography, Up From Slavery (1901), became a bestseller. Although criticized for seemingly accepting segregation, his approach built crucial institutions and created pathways for Black economic advancement during one of America's most oppressive racial periods. He was married three times and he was the father of three children (listed).