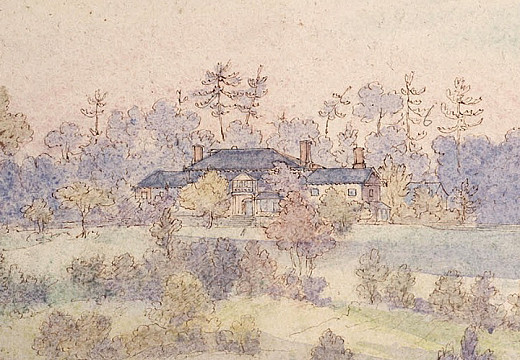

Rosedale

Rosedale, Toronto, Ontario

Built in 1824, for The Hon. William Botsford Jarvis (1799-1864) and named by his wife, Mary Boyles Powell (1803-1852). Having narrowly avoided being put to the torch during Mackenzie's Rebellion in 1837, their house was lost to urban development in 1905 but its name lives on as Toronto’s most exclusive residential district. Also sometimes referred to as "Rosedale House" or "Rosedale Villa" it stood at the intersection of Cluny Drive and Rosedale Road, facing west towards Yonge Street....

This house is best associated with...

William Botsford Jarvis was the son of Lt.-Col. Stephen Jarvis, a United Empire Loyalist from Danbury, Connecticut, who became Adjutant-General to the Forces in Upper Canada and held the sinecure post, “Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod to the Parliament of Upper Canada”. William is remembered as York’s charitable and yet “gregarious and outgoing” High Sheriff who in 1837 saw off the armed mob led by William Lyon Mackenzie. He also co-founded Yorkville with Joseph Bloor and was a Member of Parliament. He and his family were key figures in Toronto’s Conservative-Anglican elite, the “Family Compact”.

In 1796, Captain George Playter (1736-1822) received a grant at York for a 200-acre farm. In 1821, he sold 120-acres on its west side to Major John Small (1746-1831) of Berkeley House. Three years later, Small sold this farm to the 25-year old - and as yet unmarried - William Jarvis, who is not to be confused with his father’s cousin the “incompetent and dishonest” William Jarvis (1756-1817). On his newly acquired property, William built a villa suitable for attracting a wife and took up residence there with his widowed father.

Yale to Rosedale

In 1827, William was both married and appointed High Sheriff of York. His wife, Mary, had been brought up by her grandfather, William Dummer Powell (1755-1834), Chief Justice of Upper Canada. He was named for his grandmother’s brother, William Dummer (1677-1761), the Lieutenant-Governor of Massachusetts and the elder brother of Jeremiah Dummer (1681-1739) who persuaded Elihu Yale (1649-1721) to make a gift towards founding a university. John Steele Gordon wrote in American Heritage that Jeremiah’s gift was in fact the generous one, but the trustees “looking over their collective shoulder at Harvard, could not quite bring themselves to name it “Dummer College”!

The Dummers may have missed out on having a university named for their family, but their descendant, Mrs Jarvis, is remembered for giving the name "Rosedale" to what has long been Toronto’s most exclusive residential district. She named her new home for the wild roses that grew there in abundance. The house itself was remarkable for, “the romantic character of its situation on the crest of a precipitous bank overlooking deep winding ravines”.

"A Wonderful, Rambling Villa..."

In 1835, the Jarvis’ contracted Toronto’s first professional architect, John George Howard (1803-1890) to draw up plans for two new wings that were added to either side of Rosedale. These wings contained a peach house, a grape house, a conservatory, further bedrooms, a morning room and featured a large verandah. Among the hillside meadows bursting with flowers that surrounded the villa, there was a network of pathways that meandered over multiple ravines, past bird-filled hedges and through orchards, wooded enclaves and peaceful arbours.

Rosedale, the Jarvis’ 120-acre estate … was almost a northern translation of Scarlet O’Hara’s Tara; a wonderful, rambling villa perched on the edge of a (high) ravine, with a grape house and a peach house, a wildflower garden, a conservatory full of hothouse flowers, and, the envy of Toronto, a magnificent curving double staircase that descended to a hall panelled in richest walnut.

Rosedale House was approached via a lane off Yonge Street that crossed over a roughly laid plank bridge before making the steep ascent up towards the villa. In reference to its grape-house, John Gray, the head-gardener for William Henry Boulton at The Grange wrote an article entitled “Grape Culture in Canada,” published in England in 1859,

I believe the credit of having erected the first cold vinery in Toronto or its neighbourhood, and of introducing a choice collection of European grape vines, belongs to our ex-Sheriff, Wm. B. Jarvis Esq. Subsequently there was one erected at The Grange; and I believe the grapes from those two vineries have received two-thirds of the prizes awarded at our exhibitions for the last 10 or 11 years.

Both Mrs Jarvis and her eldest daughter, Fanny Jarvis (1830-1919), kept diaries. Fanny recalled her childhood at Rosedale: She kept three horses, two for her carriage (Rattler and Prince) and one (a mare called Juliet) for cross-country adventures, riding side-saddle while donning a low-crowned beaver hat with a green veil. Her summers were filled with riding parties and picnics - Toronto Island and the Humber were her favourite places.

"Down with the Sheriff, Down with Jarvis!"

On a visit to Hawkesbury, Fanny’s “never-to-be-forgotten” adventure was in bark canoes paddled by Indians through five miles of rapids down the Ottawa River. This sense of adventure served her well for when she attended finishing school in Paris during the Revolution of 1848: Rather than being afraid as most were, she watched on with excited delight as barricades were thrown up in the street! She of course remembered first-hand the angry mob led by William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861) who if he’d had his way would have put Rosedale to the torch:

The day (December 5, 1837) the rebels came into town, my brother William and I were rather seriously ill… My father was obliged to hurry away to join the troops, and my poor brave mother was enjoined not to move her sick children unless absolutely necessary… a carriage with blankets was kept in readiness.

Later in the day many rumours were brought in – first across the Ravine, Dr Horne’s house could be seen in flames… At last, the rebels rushed down Yonge Street calling, “Down with the Sheriff, down with Jarvis.” My mother thought it was time to fly. We were carried to the carriage and found our way down behind Rosedale, round Bloor’s pond and through Mr Allan’s property (Moss Park) to King Street, and on to my great-grandmother’s house on York Street.

Later on, my father heard it was Lount, one of the rebel leaders, who saved Rosedale from destruction. He halted at the hill and said if the people did not stop, he would leave them, that he was not there to fight women and children.

Sheriff Jarvis “had been obliged to hurry away” to lead a troop of 27 volunteers that came out to confront the 500-strong mob advancing up Yonge Street. After an angry exchange of words, Jarvis ordered his men to take aim. At the same time that the rebels opened fire on them, the volunteers fired back. The rebels mistook the volunteers dropping to their knees to reload as casualties and charged them. Further volleys were unleashed by Jarvis’ men who stood firm and the rebels fell back to Montgomery’s Tavern where they were later defeated.

"Mr Jarvis, Do Your Duty..."

Mackenzie escaped across the border, leaving Samuel Lount (1791-1838) and Peter Matthews (1789-1838), who had done everything to keep their “lunatic” leader from committing violent acts during those days to be captured. The Jarvis’ and most of Toronto were distraught at the inevitable cruel fate that would befall them. Rev John Ryerson (1800-1878) recorded their last moments with Jarvis:

Thursday, 12th April, Lount and Mathews were executed. The general feeling is in total opposition to the execution of those men. Sheriff Jarvis burst into tears when he entered the room to prepare them for execution. They said to him very calmly, “Mr Jarvis, do your duty; we are prepared to meet death and our Judge”. They then, both of them, put their arms around his neck and kissed him… They ascended the gallows with entire composure and firmness of step.

To round out the winter season of 1837-38, the Jarvis’ laid on a magnificent fancy-dress ball at Rosedale for 400 guests, “that a whole generation of Toronto party-goers would hold as a benchmark for the rest of their lives”. The extra efforts they went to were undoubtedly put on to lift the spirits and unite everyone following the rebellion. But, as the prosecution of Lount and Matthews was still then ongoing, one can’t help but wonder if the Jarvis’ had also hoped to use the jovial, convivial atmosphere of the party to influence the outcome of their trial.

The seven-year old Fanny Jarvis crept downstairs to witness the spectacle of 400 guests attired in a whirl of fancy-dress: Rosedale was decorated “from end-to-end” and the house was heated with extra stoves and lit with oil lanterns:

On that occasion, in the dusk of the evening, and again probably in the grey dawn of morning, an irregular procession thronged the highway of Yonge Street and toiled up and down the steep approaches to Rosedale-house – a procession consisting of the simulated shapes and forms that usually revisit the glimpses of the moon at masquerades – knights, crusaders, Plantagenet, Tudor and Stuart princes, queens and heroines; all mixed up with an incongruous ancient and modern canaille, a Tom of Bedlam, a Nicholas Bottom, “with amiable cheeks and fair large ears,” an Ariel, a Paul Pry, a Pickwick etc., etc. not pacing on with some verisimilitude on foot or respectably mounted on horse, ass, or mule, but borne along most prosaically on wheels or sleighs.

Development

In 1853, William Jarvis sold off one hundred-acres of the Rosedale estate, keeping just the house itself and its immediate 20-acres. The purchaser was his nephew, Edgar John Jarvis (1835-1907) who recognised the special charm of the area - that he named Rose Park - and planned not to build houses, but mansions to create a park-like enclave for the wealthy. Edgar subdivided the land into 62 separate lots with seven curved streets, including: Avondale, Rosedale Crescent, South Drive and Park Road. At the time, these were among the very first specifically planned-out curved roads in North America.

In 1853, William Jarvis sold off one hundred-acres of the Rosedale estate, keeping just the house itself and its immediate 20-acres. The purchaser was his nephew, Edgar John Jarvis (1835-1907) who recognised the special charm of the area - that he named Rose Park - and planned not to build houses, but mansions to create a park-like enclave for the wealthy. Edgar subdivided the land into 62 separate lots with seven curved streets, including: Avondale, Rosedale Crescent, South Drive and Park Road. At the time, these were among the very first specifically planned-out curved roads in North America.

In 1861, the Sheriff hosted a more sedate gathering at Rosedale than that of 1837:

The last surviving Canadian veterans of the War of 1812 were invited up to Rosedale to commemorate their part in the victory. Three years later, the affable, hospitable and generous Sheriff died… leaving behind him a series of debts.

The Final Chapter

The Sheriff’s children managed to cling on to the house itself, but its remaining 20-acres were subdivided and sold off to cover debts. By 1874, the house had to go too. The following year, the Sheriff’s sons, William and Robert along with their brother-in-law, Edmund Allen Meredith, regretfully sold Rosedale to Sir David Lewis Macpherson (1818-1896) of Chestnut Park. In 1879, as some form of consolation to his wife, Fanny - the young girl who had crept downstairs to watch the fancy-dress ball back in 1837 - Meredith purchased a lot on what had been the apple orchard, now 6 Rosedale Road, on which he built a spacious 22-room house where she lived out her days until 1919.

Sir David Macpherson had married one of the daughters and co-heiresses of William Molson (1793-1875), President of Molson’s Bank, who grew up at Belmont Hall. They leased out Rosedale House until 1889 when they gifted it their daughter, Christina, who lived here with her new husband, Perceval Frederick Joseph Ridout (1856-1946). In 1905, Rosedale House was demolished by order of the City to make way for Cluny Drive.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Image Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library; The Private Capital: Ambition and Love in the Age of Macdonald and Laurier (1984) by Sandra Gwyn; Toronto of Old (1873) by Henry Scadding; Estates of old Toronto (1997), by Liz Lundell; Days of the Rebels 1815-1840 (1977) by Margaret Atwood; Robertson’s Landmarks of Toronto: Sketches of the Old Town of York from 1792 until 1837, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1904 (1896) by John Ross Robertson; Mary’s Rosedale and Gossip of Little York (1928), by Alden G. Meredith; Gardeners Monthly & Horticulturist (1859), Volume 1, by Thomas Meehan. p.61 & 62; American Heritage, June 1999 – Overated & Underated by John Gordon Steele; Toronto Historical Association – Rosedale; Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada by Champlain Society, Ontario Heritgae Foundation; Edgar John Jarvis (1835-1907); Kirkpatrick family Archives