32 Fifth Avenue

Manhattan, New York

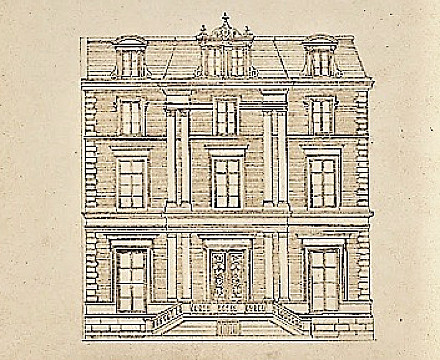

Completed in 1850, for Hart Moses Shiff (1780-1851), a German-born banker of Jewish origin from New Orleans, and his Creole wife, Marguerite Basilice de Chesse (1795-1875). Situated at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 10th Street, this was the house which its architect, Detlef Linau, used to introduce the French Second Empire style to America. Originally a free-standing building devoid of immediate neighbors, its frontage of 50-feet on Fifth Avenue was more than doubled by its depth of 126-feet. It was home to Dr Gauthier and then the Eno family before being replaced in 1924 by the Schwartz & Gross-designed high-rise that still stands at 30 Fifth Avenue....

This house is best associated with...

The Second Empire style caught the western world's imagination in Paris when Baron Haussmann lined the city's newly laid out avenues and boulevards with mansions in that style from 1852. The style is principally defined by the mansard roof and pavilion motif, both of which are perfectly evidenced on the Shiff mansion (clad in red brick and trimmed with brownstone, approached by a double staircase) which placed it at the cutting-edge of what was then modern architecture, not only in the States, but in Europe too.

Detlef Linau was the first 'American' architect who enjoyed the distinction of being a graduate of the famed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He came to New York in 1848, and just as his client, Hart M. Shiff, was an unknown newly arrived in the city but keen to make his mark on society, so too was Linau. Both German-born, Shiff and Linau endeavored to fulfil one another's ambitions. Sadly, Shiff would die in 1851, having enjoyed his new mansion for barely a year while Linau benefitted from its success for a lifetime. Just two years later, he closely replicated the facade and stamped his reputation in society when he built Beach Cliffe in Newport for society leader DeLancey Kane.

It can be assumed that as at Beach Cliffe, Linau collaborated with fellow graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, Léon Marcotte, to deliver a Louis XV-themed interior here.

Going to Gautier and onto Eno

After Shiff's death in 1851, his widow sold the mansion to Dr Josiah Hornblower Gautier, whose ancestor and namesake built the first steam engine in America. His more immediate family were all physicians and in that profession he "attained high rank" before going into business, notably steel manufacturing. However, it was his wife's money that almost certainly paid for their mansion on Fifth Avenue, she being a daughter and co-heiress of Dudley Sanford Gregory, a millionaire and U.S. Representative from New Jersey. The Gautiers lived here with their 8-children and the doctor's tenure was marked by his stubborn refusal to pave Fifth Avenue, matched by his opposition to streetcars.

Gauthier died in 1895 and two years later (1897) it was acquired by the elderly real estate baron and owner of the Fifth Avenue Hotel, Amos R. Eno. He lived here with his bachelor son, Colonel Amos F. Eno, who more than any of his other children helped manage his vast property portfolio. They divided their time between here and their family summer house in their native Connecticut, Simsbury House, but like old Mr Shiff, Eno Sr. died here just a year after moving in. Amos Jr. remained in the house, and like Dr Gautier before him, took up the torch to preserve the residential character of the district.

"One of the Finest Collections" in the Country and the "Bequest Grabbers"

Amos F. Eno accrued, "one of the finest collections" in the country of prints and early maps of New York. After his death in 1915, he left the mansion and its contents to Columbia University that, "with the single exception of the New York Historical Society, the Public Library will now have the largest collection of rare New York views extant." The Eno Collection remains one of Columbia's most precious archives and consists of hundreds of prints and early maps, "of inestimable value," notably the Visscher print of New Amsterdam printed in 1655. However, not everyone was delighted by Eno's generous bequest and his will was contested that led Columbia's lawyers to brand two of his best known nephews - Amos and Gifford Pinchot - as "bequest grabbers".

Such was the animosity, that the family sent a law clerk - John E. Merz - to the house on the premise of making an inventory of the collection, only to be found burning "hundreds of valuable documents". While the lawyers slugged the matter out in court, in 1918 the mansion was leased for $15,000 a year to hotel owner Charles F. Rogers. Two years later (1920), a new tenant was advertised for, but even with a rent reduced to $12,000, the mansion sat empty. By the time a decision had been reached in court, Columbia University succeeded in securing the Eno Collection. However, in doing so they ceded ownership of the mansion to the extended Eno family, along with losing Eno's summer home at Saratoga and relinquishing a further bequest of $1 million. In the same year (1923), the Eno family sold the mansion for development and today the 15-story red brick apartment block, numbered 30 Fifth Avenue, continues to occupy the site.

Detlef Linau was the first 'American' architect who enjoyed the distinction of being a graduate of the famed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He came to New York in 1848, and just as his client, Hart M. Shiff, was an unknown newly arrived in the city but keen to make his mark on society, so too was Linau. Both German-born, Shiff and Linau endeavored to fulfil one another's ambitions. Sadly, Shiff would die in 1851, having enjoyed his new mansion for barely a year while Linau benefitted from its success for a lifetime. Just two years later, he closely replicated the facade and stamped his reputation in society when he built Beach Cliffe in Newport for society leader DeLancey Kane.

It can be assumed that as at Beach Cliffe, Linau collaborated with fellow graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, Léon Marcotte, to deliver a Louis XV-themed interior here.

Going to Gautier and onto Eno

After Shiff's death in 1851, his widow sold the mansion to Dr Josiah Hornblower Gautier, whose ancestor and namesake built the first steam engine in America. His more immediate family were all physicians and in that profession he "attained high rank" before going into business, notably steel manufacturing. However, it was his wife's money that almost certainly paid for their mansion on Fifth Avenue, she being a daughter and co-heiress of Dudley Sanford Gregory, a millionaire and U.S. Representative from New Jersey. The Gautiers lived here with their 8-children and the doctor's tenure was marked by his stubborn refusal to pave Fifth Avenue, matched by his opposition to streetcars.

Gauthier died in 1895 and two years later (1897) it was acquired by the elderly real estate baron and owner of the Fifth Avenue Hotel, Amos R. Eno. He lived here with his bachelor son, Colonel Amos F. Eno, who more than any of his other children helped manage his vast property portfolio. They divided their time between here and their family summer house in their native Connecticut, Simsbury House, but like old Mr Shiff, Eno Sr. died here just a year after moving in. Amos Jr. remained in the house, and like Dr Gautier before him, took up the torch to preserve the residential character of the district.

"One of the Finest Collections" in the Country and the "Bequest Grabbers"

Amos F. Eno accrued, "one of the finest collections" in the country of prints and early maps of New York. After his death in 1915, he left the mansion and its contents to Columbia University that, "with the single exception of the New York Historical Society, the Public Library will now have the largest collection of rare New York views extant." The Eno Collection remains one of Columbia's most precious archives and consists of hundreds of prints and early maps, "of inestimable value," notably the Visscher print of New Amsterdam printed in 1655. However, not everyone was delighted by Eno's generous bequest and his will was contested that led Columbia's lawyers to brand two of his best known nephews - Amos and Gifford Pinchot - as "bequest grabbers".

Such was the animosity, that the family sent a law clerk - John E. Merz - to the house on the premise of making an inventory of the collection, only to be found burning "hundreds of valuable documents". While the lawyers slugged the matter out in court, in 1918 the mansion was leased for $15,000 a year to hotel owner Charles F. Rogers. Two years later (1920), a new tenant was advertised for, but even with a rent reduced to $12,000, the mansion sat empty. By the time a decision had been reached in court, Columbia University succeeded in securing the Eno Collection. However, in doing so they ceded ownership of the mansion to the extended Eno family, along with losing Eno's summer home at Saratoga and relinquishing a further bequest of $1 million. In the same year (1923), the Eno family sold the mansion for development and today the 15-story red brick apartment block, numbered 30 Fifth Avenue, continues to occupy the site.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Images from Tom Miller's excellent site, DaytonianinManhattan, Courtesy of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University