10 Washington Place

Manhattan, New York

Completed in 1846, for Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), founder of the Vanderbilt family fortune, and his first wife, Sophia Johnson (1795-1868). For the previous few years they'd lived on Staten Island at the first showpiece Vanderbilt Mansion, so when their new house was complete, Sophia cried hysterically and refused to leave. "The Commodore's" response was to put her in a mental asylum for three months, or until she changed her mind. In the end, it wasn't this violation of her freedom that forced her to move into Washington Place, it was her discovery that in her absence her husband was having an affair with their daughter's governess. For a man hoping to assert himself in genteel society but already known for coarse manners and aggressive business strategies, it was an inauspicious start and he was never accepted by his neighbors....

This house is best associated with...

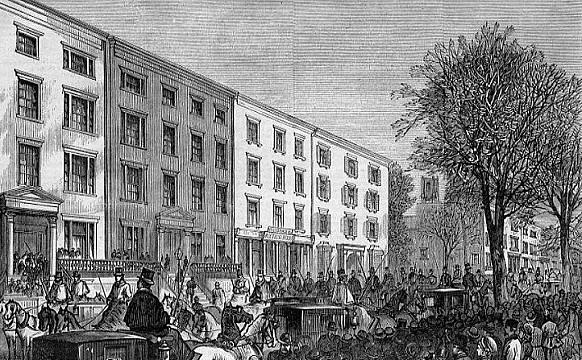

Their four-bay, red-brick home was trimmed with brownstone and took a year-and-a-half to build under the careful supervision of both Vanderbilt himself and the mason, Benjamin F. Camp. The ground on which it stood set him back $9,500 (bought from his neighbour at No. 12, Matthew Morgan) and construction costs came to $55,000. It stood four stories high over a raised basement with a frontage of 44-feet and a depth of 65 - twice the size of a normal brownstone. The stables were at the rear, separated from the house by a small paved courtyard and accessed by an entrance on Fourth Street. No.10 was reckoned to be, "one of the strongest and best constructed buildings in the city" and from the outside it was identical to No. 8, put up at the same time by George Barclay.

Ground Floor Reception Rooms

Having mounted the steps from the street and passed through the pedimented front door, the visitor would have found themselves in the lower great hall. A short distance ahead lay the foot of the main staircase and in a niche was a marble statuette of "The Commodore," a copy of the 8-foot bronze currently seen at the south facade of Grand Central Terminal.

To the right of the hall was the Drawing Room that was made up of two "large and commodious" parlors. Both rooms were, "elegantly furnished," but in contrast to Mrs Astor's House - headquarters of "the 400" whose doors back then were firmly closed to the Vanderbilts - they contained, "very few works of art". The most valuable piece on display was the marble bust of himself that Vanderbilt commissioned from Hiram Powers in Florence in 1853, now at The Breakers. Directly opposite the bust, on the other side of the room, was a statue of William Tell's son who trusted his father to shoot an arrow through an apple on his head, an act said to have triggered Swiss Independence in 1307.

Back in the hall, to the left of the staircase, a door opened onto a small reception room. This room led into the Dining Room that ran behind the staircase and extended across the width of the house, connecting back to the Drawing Room. The principal painting in the Dining Room showed Vanderbilt in a white hat driving a carriage and his favorite pair.

The Rest of the House

Ascending the staircase from the entrance hall, the visitor came out onto the landing of "the upper hall". Immediately to the right, a door opened up onto the library, "a room about twenty feet square, frescoed, and surrounded by bookcases five-and-a-half feet high". Vanderbilt's preferred genre was either historical or devotional and his favorite book that often accompanied him on his travels was Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress.

The library opened directly onto the less formal, "plain" yet "elegant" sitting room of 20-by-25-feet. Both this room and the latter overlooked Washington Place. The sitting room was where Vanderbilt felt most comfortable and where he liked to entertain his friends. Over the fireplace hung the portrait he revered the most, that of his mother; and, aside from a portrait of himself, there were two more, both of his second wife. Among the photographs on display was one of his deceased wife; one of him in the costume he wore when visiting Russia; and, another of his friend and Pastor, Charles F. Deems.

To the rear of the sitting room was a door that led into Mrs Vanderbilt's boudoir on the south side of the house. Adjoining it was a larger room that was Vanderbilt's bedroom and next to that was his "house office". The landing on the third floor gave onto four large bedrooms for family and guests, and the fourth floor - like the basement - was entirely devoted to household staff. The basement contained the kitchens, laundry rooms and what had been a billiard's room was later converted into a sitting room for the servants.

The Final Years

On January 4th, 1877, after a debilitating illness of eight months, "The Commodore" died at his home of thirty years. In accordance with his will, he left the house to his widow for her lifetime, after which it would revert to his eldest son, Billy. The widowed Mrs Vanderbilt was 45-years her husband's junior and the same age as his youngest son, but despite her comparative youth she died of pneumonia just 8-years later in May, 1885.

Billy Vanderbilt also survived his father by only 8-years, but in those few short years he managed to more than double the fortune left to him. When his stepmother died, he was happily ensconced with his family in the Vanderbilt Triple Palace on Fifth Avenue, but seven months later, he too was dead. The Commodore's house now fell into the lap of his eldest grandson, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, who back in 1877 had inherited all its statuary.

Like his father, Cornelius II, was in little need of the plain old brownstone in an area which had long since fallen out of fashion. His bolt hole in town was the iconic chateau known as the Cornelius Vanderbilt II Mansion. In 1890, he sold his grandfather's old home for $200,000 to the merchant brothers Isaac and Henry Meinhard who promptly knocked it down and replaced it with the ornate 6-story apartment store seen today.

Ground Floor Reception Rooms

Having mounted the steps from the street and passed through the pedimented front door, the visitor would have found themselves in the lower great hall. A short distance ahead lay the foot of the main staircase and in a niche was a marble statuette of "The Commodore," a copy of the 8-foot bronze currently seen at the south facade of Grand Central Terminal.

To the right of the hall was the Drawing Room that was made up of two "large and commodious" parlors. Both rooms were, "elegantly furnished," but in contrast to Mrs Astor's House - headquarters of "the 400" whose doors back then were firmly closed to the Vanderbilts - they contained, "very few works of art". The most valuable piece on display was the marble bust of himself that Vanderbilt commissioned from Hiram Powers in Florence in 1853, now at The Breakers. Directly opposite the bust, on the other side of the room, was a statue of William Tell's son who trusted his father to shoot an arrow through an apple on his head, an act said to have triggered Swiss Independence in 1307.

Back in the hall, to the left of the staircase, a door opened onto a small reception room. This room led into the Dining Room that ran behind the staircase and extended across the width of the house, connecting back to the Drawing Room. The principal painting in the Dining Room showed Vanderbilt in a white hat driving a carriage and his favorite pair.

The Rest of the House

Ascending the staircase from the entrance hall, the visitor came out onto the landing of "the upper hall". Immediately to the right, a door opened up onto the library, "a room about twenty feet square, frescoed, and surrounded by bookcases five-and-a-half feet high". Vanderbilt's preferred genre was either historical or devotional and his favorite book that often accompanied him on his travels was Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress.

The library opened directly onto the less formal, "plain" yet "elegant" sitting room of 20-by-25-feet. Both this room and the latter overlooked Washington Place. The sitting room was where Vanderbilt felt most comfortable and where he liked to entertain his friends. Over the fireplace hung the portrait he revered the most, that of his mother; and, aside from a portrait of himself, there were two more, both of his second wife. Among the photographs on display was one of his deceased wife; one of him in the costume he wore when visiting Russia; and, another of his friend and Pastor, Charles F. Deems.

To the rear of the sitting room was a door that led into Mrs Vanderbilt's boudoir on the south side of the house. Adjoining it was a larger room that was Vanderbilt's bedroom and next to that was his "house office". The landing on the third floor gave onto four large bedrooms for family and guests, and the fourth floor - like the basement - was entirely devoted to household staff. The basement contained the kitchens, laundry rooms and what had been a billiard's room was later converted into a sitting room for the servants.

The Final Years

On January 4th, 1877, after a debilitating illness of eight months, "The Commodore" died at his home of thirty years. In accordance with his will, he left the house to his widow for her lifetime, after which it would revert to his eldest son, Billy. The widowed Mrs Vanderbilt was 45-years her husband's junior and the same age as his youngest son, but despite her comparative youth she died of pneumonia just 8-years later in May, 1885.

Billy Vanderbilt also survived his father by only 8-years, but in those few short years he managed to more than double the fortune left to him. When his stepmother died, he was happily ensconced with his family in the Vanderbilt Triple Palace on Fifth Avenue, but seven months later, he too was dead. The Commodore's house now fell into the lap of his eldest grandson, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, who back in 1877 had inherited all its statuary.

Like his father, Cornelius II, was in little need of the plain old brownstone in an area which had long since fallen out of fashion. His bolt hole in town was the iconic chateau known as the Cornelius Vanderbilt II Mansion. In 1890, he sold his grandfather's old home for $200,000 to the merchant brothers Isaac and Henry Meinhard who promptly knocked it down and replaced it with the ornate 6-story apartment store seen today.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Share

The Vanderbilt Mansion, The New York Times, January 5th, 1877; The First Tycoon (2009), by T.J. Stiles; Richard Berger's 1891 No. 10 Washington Place, by Tom Miller, DaytoninManhattan