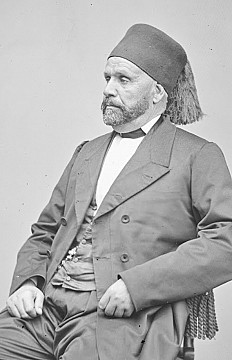

Edouard Blacque (1824-1895)

1st Turkish Ambassador to the United States

He was born to French parents but was brought up in Constantinople where his father edited Moniteur Ottoman (the first official gazette in the Ottoman Empire) and was for many years Privy Councillor to the Sultan of Turkey. After his father's premature death, Edouard and his brother were sent to Paris for their education on the instruction of their guardian, the Duc de Valmy. He joined the Ottoman Foreign service and was posted to Naples and Paris, where he met his American wife, Olivia Mott of New York. At the time of his marriage (circa 1850), he was living in Paris as private secretary to the Greek Catholic Prince Kallimake, Turkish Ambassador to the United States. When his wife died in Paris of typhus fever in 1855 he was absent on business, overseeing the construction of a telegraph line from Constantinople to Belgrade.

Shortly after Olivia's death, Edouard was the subject of a slanderous newspaper article. It claimed that Mrs Blacque had died of shock after receiving a letter from, "her absent husband, stating that he had married another wife - a Greek lady - according to his religion and the customs of his country," adding that, "he had no desire to see her again". In response, Edouard's father-in-law - New York's most distinguished surgeon of his day, Valentine Mott - sprang to his defence in a letter published in The New York Times:

"In contradiction of the false and cruel assertion of the Paris correspondent of the Daily Times... in reference to the severe bereavement to my family in the death of my daughter, Mrs Blacque, in Paris, of typhus fever, I hasten to publish a paragraph from a letter just received from her physician and my friend, Dr Bertin. It is in order to do justice to the absent... in allusion to certain uncharitable rumors which had been circulated in Paris that he says: 'I was at first induced to attribute the violent symptoms in your dear daughter's case to the moral effect of a letter received from Constantinople. Like most Americans here, I, myself, was already prejudiced; but I have since then examined the letter referred to... My conscience constrains me to say that I find nothing in it whatever which in any way could have produced the affect attributed to it". The Times was satisfied by the facts, "as conclusive evidence of the entire falsity of the statements referred to. Mr Blacque had not married another wife - neither his religion nor the customs of 'his country' would have permitted him so to do - and he wrote no such letter as is described. On the contrary, we are assured that he was in every respect a most worthy Christian gentleman, of distinguished ability and accomplishments, devoted to his wife and in every way deserving the ardent and unfaltering love which she cherished for him to her dying day."

Before his wife died, he asked the Ottoman government to establish a diplomatic post in the U.S. When it finally happened he was sent to Washington D.C. as an envoy between 1867 and 1872, by then accompanied by his second wife. Returning east, he ended his career as President (Mayor) of the Pera (modern-day Beyoglu) Municipality where he laid out a system of public parks inspired by his time in Washington, D.C.

Shortly after Olivia's death, Edouard was the subject of a slanderous newspaper article. It claimed that Mrs Blacque had died of shock after receiving a letter from, "her absent husband, stating that he had married another wife - a Greek lady - according to his religion and the customs of his country," adding that, "he had no desire to see her again". In response, Edouard's father-in-law - New York's most distinguished surgeon of his day, Valentine Mott - sprang to his defence in a letter published in The New York Times:

"In contradiction of the false and cruel assertion of the Paris correspondent of the Daily Times... in reference to the severe bereavement to my family in the death of my daughter, Mrs Blacque, in Paris, of typhus fever, I hasten to publish a paragraph from a letter just received from her physician and my friend, Dr Bertin. It is in order to do justice to the absent... in allusion to certain uncharitable rumors which had been circulated in Paris that he says: 'I was at first induced to attribute the violent symptoms in your dear daughter's case to the moral effect of a letter received from Constantinople. Like most Americans here, I, myself, was already prejudiced; but I have since then examined the letter referred to... My conscience constrains me to say that I find nothing in it whatever which in any way could have produced the affect attributed to it". The Times was satisfied by the facts, "as conclusive evidence of the entire falsity of the statements referred to. Mr Blacque had not married another wife - neither his religion nor the customs of 'his country' would have permitted him so to do - and he wrote no such letter as is described. On the contrary, we are assured that he was in every respect a most worthy Christian gentleman, of distinguished ability and accomplishments, devoted to his wife and in every way deserving the ardent and unfaltering love which she cherished for him to her dying day."

Before his wife died, he asked the Ottoman government to establish a diplomatic post in the U.S. When it finally happened he was sent to Washington D.C. as an envoy between 1867 and 1872, by then accompanied by his second wife. Returning east, he ended his career as President (Mayor) of the Pera (modern-day Beyoglu) Municipality where he laid out a system of public parks inspired by his time in Washington, D.C.