Ravenscrag

1025 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec

Built from 1863, for Sir Hugh Allan (1810-1882) and his wife Matilda Caroline Smith (1828-1881). Dominating Mount Royal as the McTavish Mansion had done before it, Ravenscrag was built for the wealthiest man in Canada and under his son it became the unequivocal centre of Montreal high society. By 1898, it had grown to 72-rooms covering 53,475 square feet - by then three times the size of Dundurn Castle and in Canada only surpassed in size by Casa Loma in 1916. Tragically, both directly and indirectly, the First World War claimed the lives of all four of the children of Sir Montagu and Lady Allan. By 1940, their fortunes had also subsided and they gifted their home to the Royal Victoria Hospital for use as a medical facility. Stripped of its former grandeur, the shell of the old mansion still stands, known today as the Allan Memorial Institute....

This house is best associated with...

Sir Hugh Allan was the second son of Sandy Allan who began life as a shoemaker before going to sea and starting what would become the Allan Shipping Line. By 1884, Hugh and his four brothers had succeeded in building the Allan Line into the 7th largest shipping line in the world, and one of the largest that was still privately owned. Under Hugh's direction, the Allan Royal Mail Steamships brought over thousands of immigrants to Canada, cementing his reputation as an empire builder. Hugh represented the family's interests in Montreal and by the time he died in 1882 he had amassed a personal fortune estimated at £8-million through his expansion into railways, communications, manufacturing and mining - all funded by his own bank, the Merchant's Bank of Canada.

Hugh was knighted in 1871 for his role in the development of ocean steam navigation, but in stark contrast to Lords Strathcona and Mount Stephen he gave nothing to charity and conditions in his mills and factories were notoriously bad even for the time: children as young as ten worked 12-hour days, barefoot through winter, earning just a dollar for a 6-day week which was often held back for fines. They were whipped by their overseers, confined to 'the blackhole' for losing time, and "apprentices were virtually slaves".

Big, But Not Yet the Biggest

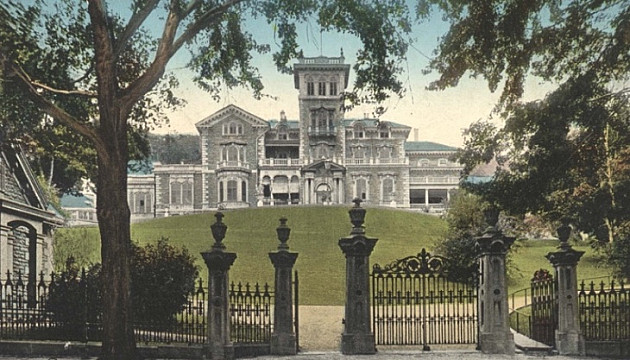

In 1860, Hugh paid £2,250 for 14-acres that had been part of the country estate of Simon McTavish. It occupied a stretch of land that ran all the way down from the mountain to Rue Sainte-Catherine. He sold off the lower portion for commercial development and chose to position his new home just north of the fabled McTavish Mansion on 10-acres that still ran a further 700-feet up the mountain. In 1861, he employed Quebec-born Victor Roy and Liverpool-born John W. Hopkins (the former working on the exterior and the latter on the interior) to build him a 34-room mansion in the fashionable Italianate style - taking its cue from Queen Victoria's Osborne House - that would dominate the slopes of Mount Royal. Its construction was supervised by William Spier & Son.

On its completion in 1863, Hugh named his new home "Ravenscrag" for the ruined tower of "Ravenscraig" in Ayrshire that was his favourite haunt when he growing up as a boy in Scotland. Ravenscrag is built of rough-faced Montreal grey-stone with smooth quoins and window surrounds. The house featured a 98-foot long conservatory as well as a ballroom measuring 60-x-46-feet with a minstrel's gallery, a billiard room and library. Its most noticeable exterior feature is the 75-foot tower which then commanded an unrivalled view over the city to the river, the Laurentians, Adirondacks and on to the Green Mountains of Vermont. But, it was the view of his ships coming in that gave Hugh the most pleasure.

Due to its size, location, and cutting-edge fashion, Ravenscrag immediately became Montreal's most talked-about new home. One journalist over-exuberantly suggested that it surpassed, "in size and cost any dwelling house in Canada, and looks more like one of the castles of the British nobility than anything we have seen here". However, in reality it was still just smaller than Dundurn Castle and although more dramatically positioned, it was no more imposing than Dundurn, Trafalgar Castle or the likes of the Caldwell Manor, Spencer Wood, the Bingham Mansion or the Chateau de Vaudreuil in their day.

"It's Like a Hotel for Servants!"

Hugh and his family lived between Ravenscrag and Belmere, their summer home on Lake Memphremagog. The Allans and their twelve children shared Ravenscrag with eleven live-in servants, once prompting the gruff capitalist who grew up in modest circumstances to exclaim, “it's like a hotel for servants!”. But eleven was just for its day-to-day running and when they entertained, depending on how many they were hosting, more were needed.

Falling From Grace

Sir Hugh and Lady Allan presided over two Royal visits: In 1869, they gave a dinner for 50 for the young Prince Arthur (the future Governor-General of Canada) who accompanied them to Belmere the following summer; and, in 1872 they carried out improvements to Ravenscrag before inviting 300-guests to a ball for the new Governor-General, the Earl of Dufferin. It was a success, but Hugh's involvement in the Pacific Scandal later that year - when he secretly colluded with Jay Cooke and bribed the Prime Minister Macdonald for a railway contract - saw him pointedly distanced from Royal and Vice-Regal society.

Changing of the Guard

Hugh's wife, Lady Matilda Allan, died in 1881 and her funeral was held in the library at Ravenscrag. Eighteen months later, Hugh died too while writing a letter at his daughter, Lady Houstoun-Boswall's, house in Edinburgh. Having all but disinherited his eldest son, Ravenscrag and the Allan fortune now fell into the hands of his second son, Montagu.

Montagu was then just a 22-year old bachelor, recently returned from Paris to round out his education. Fortunately for him, his uncle Andrew had been left in charge of the Allan family businesses which gave him time both to learn the ropes of the Allan empire, and enjoy his youth. In 1885, he gave his first ball as master of the house for 240-guests that included society from Quebec, Ottawa, New York and Boston. Hailed as, "the social event of the (Montreal) season," to give some idea of the assembled throng it was reported that the, "two conservatories which opened from the ballroom were crowded between dances".

Montagu was eventually married in 1892 to the "lively and intelligent" Marguerite Mackenzie (1873-1957) who was thirteen years his junior and had played on Ravenscrag's lawns since childhood. She was possessed of, "a taste for adventure and a mischievous sense of humour". Both her father and grandfather had filled important roles in two of the largest companies founded by Montagu's father, and yet she also had strong roots in Massachusetts being a great-granddaughter of Cyrus Alger, heavy arms manufacturer of Boston; Holmes Hinkley, founder of the Hinkley Steam Locomotive Company, Boston; and Horatio Gates, the Massachusetts-born President of the Bank of Montreal.

Coming Into Its Own

In 1889, Montagu commissioned Andrew Thomas Taylor (who the year before had dissolved his partnership with George Hamilton-Gordon in London) to enlarge the east wing of Ravenscrag. Further additions were made throughout the 1890s that saw the old portico closed and joined up with the vestibule; the Dining Room stretched out a further ten feet; and, the addition and enlargement of the veranda and several terraces and balconies to make the most of the magnificent south-facing view. Taylor was last called in 1898 to enlarge the stables for Montagu's growing collection of thoroughbreds, adding with a flourish the horse's head over the doorway and the elaborate clock.

Once Taylor was done, Ravenscrag had grown from 34 to 72 rooms and now covered 53,475-square feet over five floors, including the basement. In terms of size - though certainly not magnificence - it was now on a par with the Whitney Mansion in New York and Belle Grove in Louisiana, the largest house in the south before the Civil War.

The 10-acres of grounds were landscaped by Frederick Todd with winding pathways that led past an artificial lake for fishing with its own grotto; a vineyard; and a potting shed near to the greenhouses. From inside, an internal telephone system linked the butler's room to every obscure corner of the estate from the bedrooms to the cloakroom, sewing room, and even the greenhouse, gate lodge, stables, and tennis court.

Although Montagu and Marguerite had only four children (as opposed to Hugh's twelve), during their tenure at Ravenscrag the number of live-in servants was increased from 11, in Sir Hugh's day, to 19. This number included two governesses; a lady's maid; two liveried footmen; two housemaids; two laundresses; a cook; a scullery maid; a maid of all work; a coachman/chauffeur; three grooms; a gardener; and, a man whose sole duty it was to stoke the coal furnaces and keep the fires inside burning. They were all presided over by the Allan's English butler, Richard Chambers, and their monthly wages amounted to $575.

"A Perfect Night..."

Whereas Hugh Allan had been gruff, notoriously tight-fisted, and disliked by many, his son Montagu was popular, generous, and by all accounts a decent man. The arrival of the next generation of Allans ushered in a new era for Ravenscrag as it became the unquestioned epicentre of Montreal society until it ended with tragedy after World War I.

Unlike in New York etc., rooms set aside specifically as ballrooms were a rarity in Montreal, and despite the size and opulence of several of its mansions, the Baumgarten House was perhaps the only other in the city that could boast of such a room. As such, an invitation to a ball at Ravenscrag during this era was so highly prized that a story is told that when Sir Rodolphe Forget (1861-1919) was unable to accompany his wife to one such occasion, he was only able to console her grief after spending several thousands of dollars on a pearl necklace that was deemed the only suitable recompense.

Ravenscrag became famous for its annual New Year's Ball where the Allan's thought nothing of inviting 400-guests. In 1895, the orchestra played twenty dances (including the house waltz appropriately named "Ravenscrag") and it was recalled by one attendee as, "a perfect night... the conservatory was a dream of fragrance and beauty, rose-colored incandescent lights illuminated the masses of foliage and rare bloom and between dances many of the guests... enjoyed the cool repose of sequestered nooks under the palms". Another guest suggested that it was, "easy, even in the depths of a Canadian winter, to imagine oneself in the tropics" and when time called an end to what was deemed, "one of the most successful balls ever given in Montreal, "as the long lines of sleighs ascended the slope of the mountain, not the least beautiful sight to their occupants was that of Ravenscrag itself, outlined in points of light against the dark background of Mount Royal".

Still the Faint Whiff of Scandal

Even twenty years after the death of Sir Hugh, the next generation of Allans were still tainted by his fall from grace which in 1901 presented the Governor-General (the Earl of Minto) with something of a diplomatic quandary: Lord Strathcona had invited the future King George V and Queen Mary to Canada as part of a Royal Party that included Prince Alexander of Teck and no less than 47 of their accompanying staff and servants.

Exasperated by where to house them in Montreal, Minto turned to Sir Edward Clouston for advice, bemoaning, "you know how small his (Strathcona's) house is". Montagu Allan in the meantime offered up all of Ravenscrag for the Royal Party, but Minto did not even deign to consider what would have been a perfect solution. Instead, the Royals were stuffed into Strathcona's guest house in the west wing of the Shaughnessy House while staff members were put up at the R.B. Angus House and servants were given rooms at Royal Victoria College - hardly an ideal set up, but a strong indication of Minto's disdain.

Beacon of Montreal Society

Excepting Lord Minto's traditionalisms (he didn't approve of the changes in ladies' fashion and perhaps found Lady Allan not quite enough of a flower on the wall), Ravenscrag was still very much the focal point of Montreal society: In 1904, Montagu was knighted by King Edward VII and the following year he was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order; the Union Jack flew from the tower; the Montreal Hunt met here several times during the season to start their day with a hunt breakfast; and, before dusk, attired in colourful sashes ("very picturesque, very Canadian" commented the Countess of Dufferin), the members of the Montreal Snow Shoe Club gathered here with torches before taking off up the mountain to form, "a fiery serpent winding among the trees".

Another ball was given in 1906 for Prince Arthur, now the Duke of Connaught, who no doubt would have been interested to have seen how the house had grown since his last visit in 1869; and, the following year, the Allans entertained Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, brother of the Mikado of Japan, when they converted a suite of rooms that was kept reserved for Royalty. The next time they were used was for less fortunate circumstances: the Duchess of Connaught was taken ill in January, 1913, and while she was being treated at the Royal Victoria Hospital the Allans vacated to the J.K.L. Ross House to allow for her husband and daughter to stay at Ravenscrag. Similarly, when Lady Bessborough gave birth in 1931, the Allans allowed the Vice-Regal family the use of their home.

Tragedy, and the End of the Allan Line

World War I all but broke the Allans. Like everyone else, they started the war full of enterprise and optimism but tragedy first struck in 1915 when Lady Allan was unable to save her two youngest teenage daughters (Gwen and Anna) who drowned when their steamship, the Lusitania, was infamously torpedoed by the Germans. Two years later, their only son, Hugh, was killed in his first combat mission with the Royal Naval Air Service. Their only surviving daughter, Martha, would live on until 1942 but she too predeceased her parents when she succumbed to ill-health, an indirect victim of the same war having caught pneumonia as a nurse and ambulance driver in France.

Deprived of his son and heir in 1917, Sir Montagu sold his remaining shares in what had been the Allan Steamship Line, which had in fact already been sold in utmost secrecy in 1909 and was publicly amalgamated with the Canadian Pacific Steamship Co. in 1915. For the duration of the war, Marguerite and Martha devoted their time and fortune to the 140-bed Moor Park Convalescent Home at Sidmouth, Devon, and established "Maple Leaf Clubs" for Canadian soldiers coming back from the Front on leave. Montagu also lived at Moor Park while he set up a Pension scheme for disabled Canadian soldiers, and from 1916 he rented Ravenscrag to the new Governor-General of Canada, the Duke of Devonshire.

"Victorian Guilt"

The first thing to greet the Devonshires as they walked into Ravenscrag were the photographs of Gwen and Anna, doing little to alleviate the "oppressive" sensation they felt here. The Duchess was not complementary, observing: "Every available space which is not filled with a Victorian guilt [sic] mirror is painted with a fat cupid. The ceilings are adorned with Greek Gods and Goddesses from among whom hang glass chandeliers... On a background of varnished wood panelling hangs the portrait of Sir Montagu Allan in hunting costume... On to all of this add the fact that the architect thought windows superfluous, that the plumber thought that cold water coming through the neck and beak of a swan into one's bath preferable to hot water coming through an ordinary tap".

The Last Hurrah

The Allans did not return to Canada until 1919, but their troubles were not over. In 1922, the Merchant's Bank of Canada - that other stalwart of the Allan family into which Sir Montagu had put all their remaining interests after selling the Allan Line - was declared insolvent. To keep his head above water, he sold off his weekend home in Beaconsfield, Allancroft, but managed to hold on to his summer home in Cacouna, Montrose.

For the good of their own spirits and those who had looked up to them before the war, the Allans - Montagu, Marguerite and Martha - continued to maintain a cheerful facade. Lady Allan hosted only one ball between the two world wars, but that wasn't to say the fun had stopped - it was the Roaring Twenties after all. In the 1920s, the Prince of Wales - thoroughly unsuccessful in his bid to travel incognito as 'Lord Renfrew' - became a not irregular face in Montreal society and may have been at Ravenscrag for, "one memorable party when the dancer 'Argentina' held court in the ballroom, while in the library bridge was played, and in the Drawing Room Sir Henry Thornton, the big jovial president of Canadian National Railways, was found imitating the love dance of an elephant".

In the meantime, Martha made her home in the old stables and, using the space for meetings and rehearsals, threw herself into theatre which she had previously studied in Paris. Described as, "immensely self-assured, forceful and resourceful, with all manner of charm," Martha founded the Montreal Repertory Theatre (MRT) that acted as a springboard for the careers of several notable actors, including Christoper Plummer whose great-grandfather, Sir John Abbott, had been Sir Hugh Allan's lawyer.

"In the Front Hall a Barometer Pointed to 'Change'..."

By 1938, property taxes alone on Ravenscrag (then valued between $400-$450,000) had reached a dizzying $50,000 a year and the Allans finally swapped mansion life for an apartment in "Le Château" on Sherbrooke Street. On the outbreak of war in 1939, they offered Ravenscrag to the Canadian government but having no use for it their offer was politely refused. The following year, they successfully gifted the old house to the Royal Victoria Hospital for use as a convalescent home and on a cold, grey, slushy day in November the remaining contents of Ravenscrag were sold off at auction.

That day saw items carried out such as mounted antelope heads; candelabra held aloft by life-size caryatids (female statues); elephants carved from ivory and ebony; a small gallery's worth of paintings; monogrammed bedding; furniture that included brocaded sofas and chairs; impossibly long corridor carpets; wardrobes larger than a room in a normal house; 5-bathtubs that could each hold a small family; the internal telephone system; and, a garden statue of the Greek god Pan while, "in the front hall a barometer pointed to 'change'. The floor of the conservatory was strewn with dead leaves."

Sir Montagu Allan died in 1951. He'd lost all four of his children, none of whom married nor had children of their own; he'd lost the businesses on which the family fortune was made; and, he'd lost the family house. Nonetheless, he and Marguerite (who died in 1957) remained generous and cheerful to the end. Martha's legacy is the National Theatre School, but the Allans would have been horrified by what happened in their home next.

The Allan Memorial Institute and MK-ULTRA

In 1943, Ravenscrag was repurposed as the Allan Memorial Institute for psychiatric patients. During the Cold War, it was selected by the CIA as one of several psychiatric institutions across North America where they funded secret mind-control experiments on otherwise healthy and unwitting Canadians through the use of psychedelic drugs, sensory deprivation, electroshock treatment and more. The now infamous programme conducted between 1957 and 1964 was codenamed MK-ULTRA and laid the groundwork for modern-day torture techniques. Today, "The Allan" - a shell of its former glory but a respected institution - houses outpatient psychiatric services for the Montreal General Hospital.

Hugh was knighted in 1871 for his role in the development of ocean steam navigation, but in stark contrast to Lords Strathcona and Mount Stephen he gave nothing to charity and conditions in his mills and factories were notoriously bad even for the time: children as young as ten worked 12-hour days, barefoot through winter, earning just a dollar for a 6-day week which was often held back for fines. They were whipped by their overseers, confined to 'the blackhole' for losing time, and "apprentices were virtually slaves".

Big, But Not Yet the Biggest

In 1860, Hugh paid £2,250 for 14-acres that had been part of the country estate of Simon McTavish. It occupied a stretch of land that ran all the way down from the mountain to Rue Sainte-Catherine. He sold off the lower portion for commercial development and chose to position his new home just north of the fabled McTavish Mansion on 10-acres that still ran a further 700-feet up the mountain. In 1861, he employed Quebec-born Victor Roy and Liverpool-born John W. Hopkins (the former working on the exterior and the latter on the interior) to build him a 34-room mansion in the fashionable Italianate style - taking its cue from Queen Victoria's Osborne House - that would dominate the slopes of Mount Royal. Its construction was supervised by William Spier & Son.

On its completion in 1863, Hugh named his new home "Ravenscrag" for the ruined tower of "Ravenscraig" in Ayrshire that was his favourite haunt when he growing up as a boy in Scotland. Ravenscrag is built of rough-faced Montreal grey-stone with smooth quoins and window surrounds. The house featured a 98-foot long conservatory as well as a ballroom measuring 60-x-46-feet with a minstrel's gallery, a billiard room and library. Its most noticeable exterior feature is the 75-foot tower which then commanded an unrivalled view over the city to the river, the Laurentians, Adirondacks and on to the Green Mountains of Vermont. But, it was the view of his ships coming in that gave Hugh the most pleasure.

Due to its size, location, and cutting-edge fashion, Ravenscrag immediately became Montreal's most talked-about new home. One journalist over-exuberantly suggested that it surpassed, "in size and cost any dwelling house in Canada, and looks more like one of the castles of the British nobility than anything we have seen here". However, in reality it was still just smaller than Dundurn Castle and although more dramatically positioned, it was no more imposing than Dundurn, Trafalgar Castle or the likes of the Caldwell Manor, Spencer Wood, the Bingham Mansion or the Chateau de Vaudreuil in their day.

"It's Like a Hotel for Servants!"

Hugh and his family lived between Ravenscrag and Belmere, their summer home on Lake Memphremagog. The Allans and their twelve children shared Ravenscrag with eleven live-in servants, once prompting the gruff capitalist who grew up in modest circumstances to exclaim, “it's like a hotel for servants!”. But eleven was just for its day-to-day running and when they entertained, depending on how many they were hosting, more were needed.

Falling From Grace

Sir Hugh and Lady Allan presided over two Royal visits: In 1869, they gave a dinner for 50 for the young Prince Arthur (the future Governor-General of Canada) who accompanied them to Belmere the following summer; and, in 1872 they carried out improvements to Ravenscrag before inviting 300-guests to a ball for the new Governor-General, the Earl of Dufferin. It was a success, but Hugh's involvement in the Pacific Scandal later that year - when he secretly colluded with Jay Cooke and bribed the Prime Minister Macdonald for a railway contract - saw him pointedly distanced from Royal and Vice-Regal society.

Changing of the Guard

Hugh's wife, Lady Matilda Allan, died in 1881 and her funeral was held in the library at Ravenscrag. Eighteen months later, Hugh died too while writing a letter at his daughter, Lady Houstoun-Boswall's, house in Edinburgh. Having all but disinherited his eldest son, Ravenscrag and the Allan fortune now fell into the hands of his second son, Montagu.

Montagu was then just a 22-year old bachelor, recently returned from Paris to round out his education. Fortunately for him, his uncle Andrew had been left in charge of the Allan family businesses which gave him time both to learn the ropes of the Allan empire, and enjoy his youth. In 1885, he gave his first ball as master of the house for 240-guests that included society from Quebec, Ottawa, New York and Boston. Hailed as, "the social event of the (Montreal) season," to give some idea of the assembled throng it was reported that the, "two conservatories which opened from the ballroom were crowded between dances".

Montagu was eventually married in 1892 to the "lively and intelligent" Marguerite Mackenzie (1873-1957) who was thirteen years his junior and had played on Ravenscrag's lawns since childhood. She was possessed of, "a taste for adventure and a mischievous sense of humour". Both her father and grandfather had filled important roles in two of the largest companies founded by Montagu's father, and yet she also had strong roots in Massachusetts being a great-granddaughter of Cyrus Alger, heavy arms manufacturer of Boston; Holmes Hinkley, founder of the Hinkley Steam Locomotive Company, Boston; and Horatio Gates, the Massachusetts-born President of the Bank of Montreal.

Coming Into Its Own

In 1889, Montagu commissioned Andrew Thomas Taylor (who the year before had dissolved his partnership with George Hamilton-Gordon in London) to enlarge the east wing of Ravenscrag. Further additions were made throughout the 1890s that saw the old portico closed and joined up with the vestibule; the Dining Room stretched out a further ten feet; and, the addition and enlargement of the veranda and several terraces and balconies to make the most of the magnificent south-facing view. Taylor was last called in 1898 to enlarge the stables for Montagu's growing collection of thoroughbreds, adding with a flourish the horse's head over the doorway and the elaborate clock.

Once Taylor was done, Ravenscrag had grown from 34 to 72 rooms and now covered 53,475-square feet over five floors, including the basement. In terms of size - though certainly not magnificence - it was now on a par with the Whitney Mansion in New York and Belle Grove in Louisiana, the largest house in the south before the Civil War.

The 10-acres of grounds were landscaped by Frederick Todd with winding pathways that led past an artificial lake for fishing with its own grotto; a vineyard; and a potting shed near to the greenhouses. From inside, an internal telephone system linked the butler's room to every obscure corner of the estate from the bedrooms to the cloakroom, sewing room, and even the greenhouse, gate lodge, stables, and tennis court.

Although Montagu and Marguerite had only four children (as opposed to Hugh's twelve), during their tenure at Ravenscrag the number of live-in servants was increased from 11, in Sir Hugh's day, to 19. This number included two governesses; a lady's maid; two liveried footmen; two housemaids; two laundresses; a cook; a scullery maid; a maid of all work; a coachman/chauffeur; three grooms; a gardener; and, a man whose sole duty it was to stoke the coal furnaces and keep the fires inside burning. They were all presided over by the Allan's English butler, Richard Chambers, and their monthly wages amounted to $575.

"A Perfect Night..."

Whereas Hugh Allan had been gruff, notoriously tight-fisted, and disliked by many, his son Montagu was popular, generous, and by all accounts a decent man. The arrival of the next generation of Allans ushered in a new era for Ravenscrag as it became the unquestioned epicentre of Montreal society until it ended with tragedy after World War I.

Unlike in New York etc., rooms set aside specifically as ballrooms were a rarity in Montreal, and despite the size and opulence of several of its mansions, the Baumgarten House was perhaps the only other in the city that could boast of such a room. As such, an invitation to a ball at Ravenscrag during this era was so highly prized that a story is told that when Sir Rodolphe Forget (1861-1919) was unable to accompany his wife to one such occasion, he was only able to console her grief after spending several thousands of dollars on a pearl necklace that was deemed the only suitable recompense.

Ravenscrag became famous for its annual New Year's Ball where the Allan's thought nothing of inviting 400-guests. In 1895, the orchestra played twenty dances (including the house waltz appropriately named "Ravenscrag") and it was recalled by one attendee as, "a perfect night... the conservatory was a dream of fragrance and beauty, rose-colored incandescent lights illuminated the masses of foliage and rare bloom and between dances many of the guests... enjoyed the cool repose of sequestered nooks under the palms". Another guest suggested that it was, "easy, even in the depths of a Canadian winter, to imagine oneself in the tropics" and when time called an end to what was deemed, "one of the most successful balls ever given in Montreal, "as the long lines of sleighs ascended the slope of the mountain, not the least beautiful sight to their occupants was that of Ravenscrag itself, outlined in points of light against the dark background of Mount Royal".

Still the Faint Whiff of Scandal

Even twenty years after the death of Sir Hugh, the next generation of Allans were still tainted by his fall from grace which in 1901 presented the Governor-General (the Earl of Minto) with something of a diplomatic quandary: Lord Strathcona had invited the future King George V and Queen Mary to Canada as part of a Royal Party that included Prince Alexander of Teck and no less than 47 of their accompanying staff and servants.

Exasperated by where to house them in Montreal, Minto turned to Sir Edward Clouston for advice, bemoaning, "you know how small his (Strathcona's) house is". Montagu Allan in the meantime offered up all of Ravenscrag for the Royal Party, but Minto did not even deign to consider what would have been a perfect solution. Instead, the Royals were stuffed into Strathcona's guest house in the west wing of the Shaughnessy House while staff members were put up at the R.B. Angus House and servants were given rooms at Royal Victoria College - hardly an ideal set up, but a strong indication of Minto's disdain.

Beacon of Montreal Society

Excepting Lord Minto's traditionalisms (he didn't approve of the changes in ladies' fashion and perhaps found Lady Allan not quite enough of a flower on the wall), Ravenscrag was still very much the focal point of Montreal society: In 1904, Montagu was knighted by King Edward VII and the following year he was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order; the Union Jack flew from the tower; the Montreal Hunt met here several times during the season to start their day with a hunt breakfast; and, before dusk, attired in colourful sashes ("very picturesque, very Canadian" commented the Countess of Dufferin), the members of the Montreal Snow Shoe Club gathered here with torches before taking off up the mountain to form, "a fiery serpent winding among the trees".

Another ball was given in 1906 for Prince Arthur, now the Duke of Connaught, who no doubt would have been interested to have seen how the house had grown since his last visit in 1869; and, the following year, the Allans entertained Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, brother of the Mikado of Japan, when they converted a suite of rooms that was kept reserved for Royalty. The next time they were used was for less fortunate circumstances: the Duchess of Connaught was taken ill in January, 1913, and while she was being treated at the Royal Victoria Hospital the Allans vacated to the J.K.L. Ross House to allow for her husband and daughter to stay at Ravenscrag. Similarly, when Lady Bessborough gave birth in 1931, the Allans allowed the Vice-Regal family the use of their home.

Tragedy, and the End of the Allan Line

World War I all but broke the Allans. Like everyone else, they started the war full of enterprise and optimism but tragedy first struck in 1915 when Lady Allan was unable to save her two youngest teenage daughters (Gwen and Anna) who drowned when their steamship, the Lusitania, was infamously torpedoed by the Germans. Two years later, their only son, Hugh, was killed in his first combat mission with the Royal Naval Air Service. Their only surviving daughter, Martha, would live on until 1942 but she too predeceased her parents when she succumbed to ill-health, an indirect victim of the same war having caught pneumonia as a nurse and ambulance driver in France.

Deprived of his son and heir in 1917, Sir Montagu sold his remaining shares in what had been the Allan Steamship Line, which had in fact already been sold in utmost secrecy in 1909 and was publicly amalgamated with the Canadian Pacific Steamship Co. in 1915. For the duration of the war, Marguerite and Martha devoted their time and fortune to the 140-bed Moor Park Convalescent Home at Sidmouth, Devon, and established "Maple Leaf Clubs" for Canadian soldiers coming back from the Front on leave. Montagu also lived at Moor Park while he set up a Pension scheme for disabled Canadian soldiers, and from 1916 he rented Ravenscrag to the new Governor-General of Canada, the Duke of Devonshire.

"Victorian Guilt"

The first thing to greet the Devonshires as they walked into Ravenscrag were the photographs of Gwen and Anna, doing little to alleviate the "oppressive" sensation they felt here. The Duchess was not complementary, observing: "Every available space which is not filled with a Victorian guilt [sic] mirror is painted with a fat cupid. The ceilings are adorned with Greek Gods and Goddesses from among whom hang glass chandeliers... On a background of varnished wood panelling hangs the portrait of Sir Montagu Allan in hunting costume... On to all of this add the fact that the architect thought windows superfluous, that the plumber thought that cold water coming through the neck and beak of a swan into one's bath preferable to hot water coming through an ordinary tap".

The Last Hurrah

The Allans did not return to Canada until 1919, but their troubles were not over. In 1922, the Merchant's Bank of Canada - that other stalwart of the Allan family into which Sir Montagu had put all their remaining interests after selling the Allan Line - was declared insolvent. To keep his head above water, he sold off his weekend home in Beaconsfield, Allancroft, but managed to hold on to his summer home in Cacouna, Montrose.

For the good of their own spirits and those who had looked up to them before the war, the Allans - Montagu, Marguerite and Martha - continued to maintain a cheerful facade. Lady Allan hosted only one ball between the two world wars, but that wasn't to say the fun had stopped - it was the Roaring Twenties after all. In the 1920s, the Prince of Wales - thoroughly unsuccessful in his bid to travel incognito as 'Lord Renfrew' - became a not irregular face in Montreal society and may have been at Ravenscrag for, "one memorable party when the dancer 'Argentina' held court in the ballroom, while in the library bridge was played, and in the Drawing Room Sir Henry Thornton, the big jovial president of Canadian National Railways, was found imitating the love dance of an elephant".

In the meantime, Martha made her home in the old stables and, using the space for meetings and rehearsals, threw herself into theatre which she had previously studied in Paris. Described as, "immensely self-assured, forceful and resourceful, with all manner of charm," Martha founded the Montreal Repertory Theatre (MRT) that acted as a springboard for the careers of several notable actors, including Christoper Plummer whose great-grandfather, Sir John Abbott, had been Sir Hugh Allan's lawyer.

"In the Front Hall a Barometer Pointed to 'Change'..."

By 1938, property taxes alone on Ravenscrag (then valued between $400-$450,000) had reached a dizzying $50,000 a year and the Allans finally swapped mansion life for an apartment in "Le Château" on Sherbrooke Street. On the outbreak of war in 1939, they offered Ravenscrag to the Canadian government but having no use for it their offer was politely refused. The following year, they successfully gifted the old house to the Royal Victoria Hospital for use as a convalescent home and on a cold, grey, slushy day in November the remaining contents of Ravenscrag were sold off at auction.

That day saw items carried out such as mounted antelope heads; candelabra held aloft by life-size caryatids (female statues); elephants carved from ivory and ebony; a small gallery's worth of paintings; monogrammed bedding; furniture that included brocaded sofas and chairs; impossibly long corridor carpets; wardrobes larger than a room in a normal house; 5-bathtubs that could each hold a small family; the internal telephone system; and, a garden statue of the Greek god Pan while, "in the front hall a barometer pointed to 'change'. The floor of the conservatory was strewn with dead leaves."

Sir Montagu Allan died in 1951. He'd lost all four of his children, none of whom married nor had children of their own; he'd lost the businesses on which the family fortune was made; and, he'd lost the family house. Nonetheless, he and Marguerite (who died in 1957) remained generous and cheerful to the end. Martha's legacy is the National Theatre School, but the Allans would have been horrified by what happened in their home next.

The Allan Memorial Institute and MK-ULTRA

In 1943, Ravenscrag was repurposed as the Allan Memorial Institute for psychiatric patients. During the Cold War, it was selected by the CIA as one of several psychiatric institutions across North America where they funded secret mind-control experiments on otherwise healthy and unwitting Canadians through the use of psychedelic drugs, sensory deprivation, electroshock treatment and more. The now infamous programme conducted between 1957 and 1964 was codenamed MK-ULTRA and laid the groundwork for modern-day torture techniques. Today, "The Allan" - a shell of its former glory but a respected institution - houses outpatient psychiatric services for the Montreal General Hospital.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Images Courtesy of the McCord Museum, Montreal; Lord Strathcona: A Biography of Donald Alexander Smith by Donna McDonald; Thomas1313's excellent piece on French Wikipedia; Ravenscrag (1985), by Robert Bianchini for the McGill University School of Architecture; At Ravenscrag, Montreal Daily Herald, January 2, 1895; Ravenscrag’s Halls Come to Life As Rich Furnishings Go on Block, by Tracy Ludington; Sir Hugh Allan and his House on the Hill, The Record, 1984; Lusitania: Triumph, Tragedy, and the End of the Edwardian Age, by Greg King & Penny Wilson; Victor and Evie: British Aristocrats in Wartime Rideau Hall (2017) by Dorothy Anne Phillips; Nobesse Oblige, by Rob Paterson; The Square Mile, by Donald McKay; MK-ULTRA: The CIA's Secret Pursuit of Mind-Control, BBC; Passenger and Merchant Ships of the Grand Trunk Pacific and Canadian Northern Railways (2016) by David R.P. Guay